EBITDA, short for Earnings Before Interest, Taxation, Depreciation & Amoritization, is a popular way technology companies like to value themselves. It is not a GAAP term. Instead, GAAP insists on using Net Income, the proverbial "bottomeline."

Why do tech companies prefer EBITDA over Net Income? The dilemma has been around a long time. Consider Warren Buffett's screeds on EBITDA. Charlie Munger likens it to "bullshit earnings."

This seems a bit harsh. The bulk of the criticism is on EBITDA ignoring Amortization and Depreciation. Both Munger & Buffett consider these crucial values to include. Interestingly, Buffett mentions that some businesses can get away with ignoring it. This put me down a rabbit hole.

Buffett & Co. have traditionally invested in companies with large fixed assets. This includes brick making companies, underwear producers, and railroads. In accounting, large fixed assets are added to gross profits via Depreciation and Amortization -- the D & A of EBITDA. This is because they are required by the business to function and must be replaced on a regular interval. To convey this importance, they get added to gross income, revenue after expenses and COGS, divided over their useful life.

For businesses like railroads, this makes a lot of sense. A given railroad car may have 20 years of useful life before its junked and replaced. It shouldn't be ignored: if the railroad has no cars, it can't do business. The cost is essential when looking at the health of the company. In an extreme hypothetical, you may have a railroad posting outstanding EBITDA one quarter only to go bankrupt the next because all the cars needed to be replaced.

As Buffett mentioned, some companies are different. Take technology firms, whose business model often sits on having large fixed costs to make or develop a product and low variable costs to produce an distribute. Some technology companies behave like a railroad here. Think Tesla with its large factories. But others don't. These include software companies. They don't have large assets to amoritize or depreciate. Software is effectively free to replicate. The fixed cost of writing it is instead expensed via R&D due to the ongoing nature of upkeep (e.g. Microsoft Word gets updated every year).

Does Berkshire Hathaway invest in technology companies? Not really. They're added positions in Apple and Amazon in recent years but typically have shied away from "new world" companies on the basis of not fully understanding them (i.e. circle of competency thinking).

Does that mean EBITDA is good enough for software businesses? Maybe. There's two other components to consider though. Taxation can be an expense but is a bit more difficult to factor in a simple way. It's more dependent on the company itself and its legal structure.

What about Interest? This is where things get more interesting.

Private tech companies rarely have much debt and what debt they do raise is usually a convertible bond (i.e. becomes stock instead of being repaid). Public companies do raise a lot of debt, especially ones with odd unit economics.

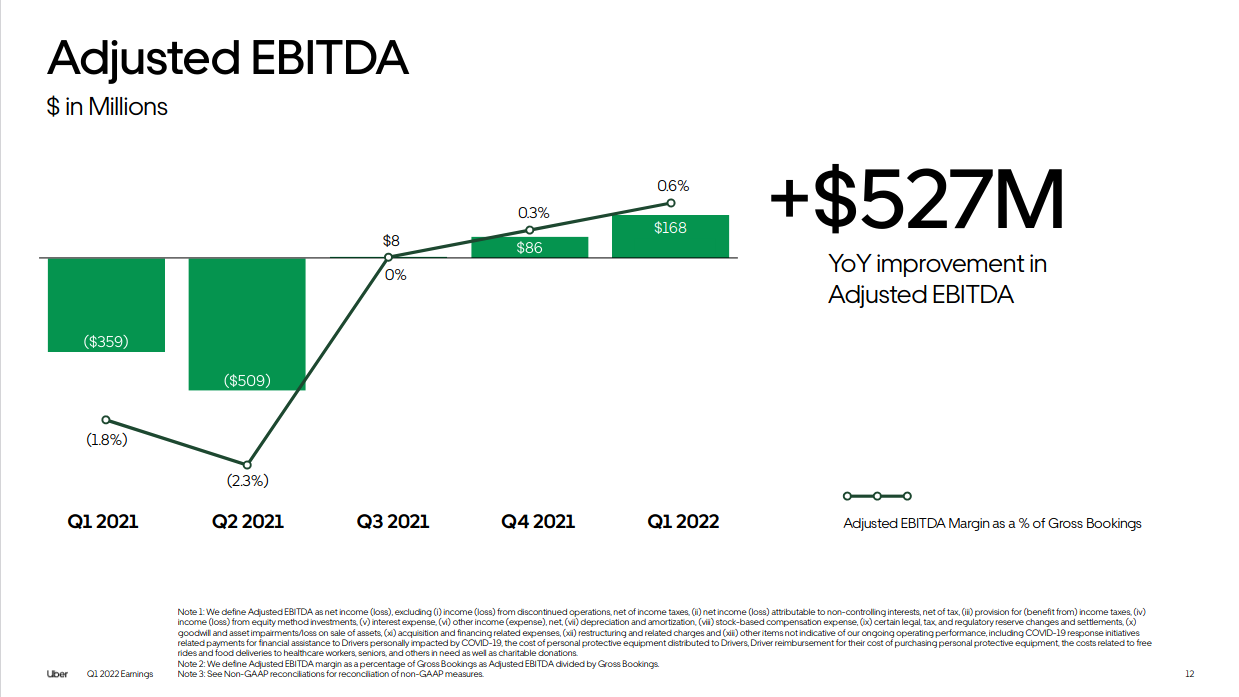

Look at Uber. It's EBITDA looks healthy.

They don't have many assets to depreciate or amortize. But they do have a lot of interest from debt.

So should EBITDA be ignored? Uber is also an odd technology company. They don't sell software but a service powered by software so the cost of replicating that service is not free. Their debt load, and the interest they pay on it, is not as healthy.

The choice is yours at the end of the day. EBITDA can tell you a lot about a business but its hardly an end-all-be-all. Net Income can be a bit premature if the company is not established and still in the startup phase.